Howdy! I’m Erich Schnack, I’m a Cleveland State University graduate and Yosemite National Park Ranger. I earned my B.A. in History and Social Studies at Cleveland State University’s Jack Joseph & Morton Mandel Honor’s College in 2020. In 2022, I earned a History/Museum Studies M.A. and Historic Preservation graduate certificate from Cleveland State University.

It was one cold winter night in 2018 around 3 a.m. I found myself nervously scrambling to find a career path with my history degree that didn’t involve teaching. In my quest, I noticed there was an internship opportunity at the Cuyahoga Valley National Park for Community Engagement. I’ve always had a passion for the outdoors and the wonders of nature. Hiking, climbing, backpacking, or a quick prance around the Cuyahoga Valley National Park or Cleveland Metroparks. I had come to the conclusion that I could not work inside every day. The nail in the coffin were the two summer long road trips I took following the jam band Dead & Company, essentially living in National Parks and National Forests between shows. With my romantic admiration for public lands, I jumped at the opportunity and worked the summer of 2019 doing community outreach, guided hikes, and fishing programs. In 2020, I was recruited as an Interpretive Park Ranger for the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. My duties were similar to those of my internship. In time, my duties would expand into public history and oral histories, with the support of co-workers and some sweat on the brow.

In 2021, I was one of Dr. Souther’s graduate students in his public history class. The focus of the class was Green Book Cleveland, a project aimed at documenting Black leisure and recreation in Northeast Ohio. As both a Cleveland State student and a Park Ranger, I researched Black recreational sites in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park (Lake Glen, Cabin Club, Stonibrook). These were integrated into web articles, community programming, and the park’s interpretive theme framework.

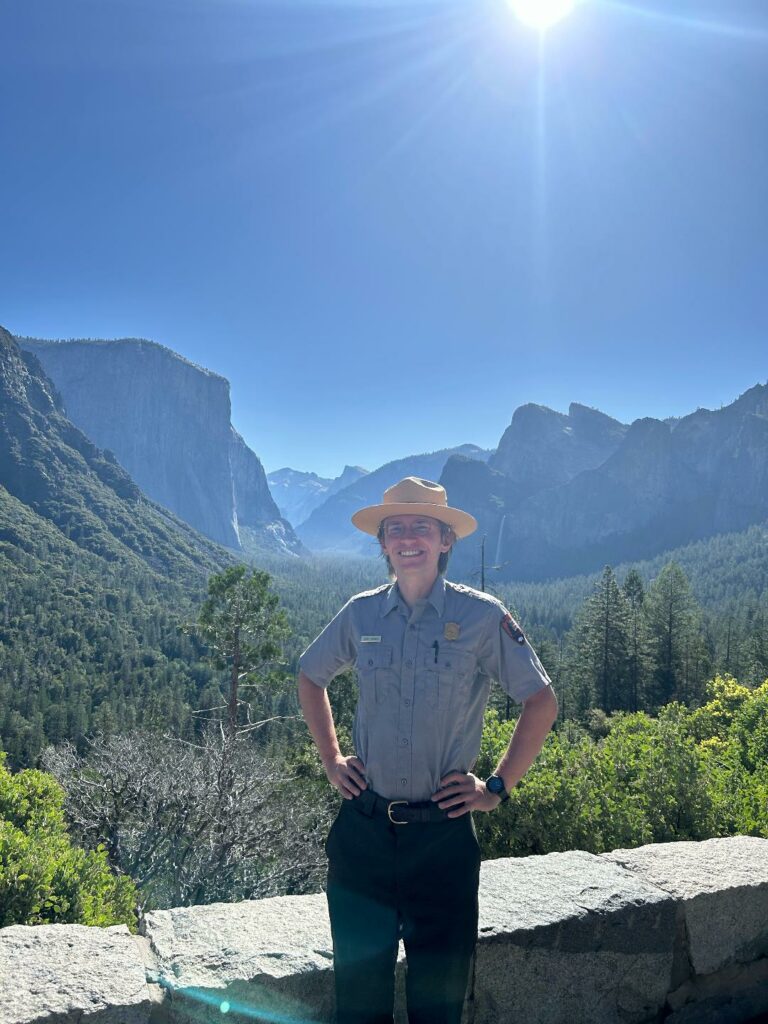

In October 2023, I applied to be a seasonal Yosemite National Park Ranger, and by April 2024, I was headed out west. The opportunity wouldn’t have been possible without the support of my Cuyahoga Valley National Park supervisor, Pam Machuga, all my Cuyahoga Valley National Park co-workers, and Dr. Souther at the helm of the Green Book Cleveland project. I am eternally grateful for each person who has helped me reach the land John Muir described as “by far the grandest of all of the special temples of Nature I was ever permitted to enter.”

Yosemite has been good to this fella from Cuyahoga Valley. The new sights, friends, and memories will always be cherished. There are jubilations at campfire gatherings nearly every night. Hiking, climbing, and cold plunges are abound. The spicy smell of the incense cedar tree fills the air. Every day, as I step out with my morning coffee, I’m greeted by a pileated woodpecker finding his morning meal. I’m deeply grateful to be among a talented, brilliant, and whimsical group of fellow interpretive rangers. My duties include guided hikes of the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, campfire programs, Jr. Ranger programs, and visitor center duties.

Being a history graduate, or as I timidly call myself, a historian.. My summer goal is to bring a new story to light. Years ago, I read that Yosemite National Park and other public lands had been “invaded” by hippies in 1970 after the tragic fall of San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury in 1969 (the proverbial mecca of the hippie counterculture). The Diggers provided free food, there were free clinics, and the music of Jimi Hendrix, Grateful Dead, The Doors and Janis Joplin rang from street to street. The subsequent public land “invasion” led to a clash between traditional visitors, rangers, and the counterculture. This clash was a microcosm of the whole nation. In the late 1960s, the anti-war movement, the Civil Rights movement, the environmental movement, new feminist movements, and new ideas of sexual liberation frightened mainstream America. Communal living, experimentation with psychedelic drugs, and a general tendency towards anti-authoritarianism set the stage for a series of events that led to a riot at Yosemite on July 4, 1970. The Berkeley Tribe, a popular Berkely magazine, described Yosemite as an “occupied zone.” Rangers claimed that hippies were disturbing the integrity of the park. For two months in preparation for Labor Day, the Park Service denied entry to men with long hair, Volkswagen buses, and anyone who fit the profile. They also met with the U.S. Marshalls, the CIA, and local law enforcement for a “Labor Day War.” The war never happened. In 1971, the National Park Service admitted that the riot was a mistake. They began accommodating the new tie-dyed visitor with a whole gamut of new programming. Ecology talks rather than “Yosemite’s Great American Story”, yoga classes, arts and crafts, and even slideshow pictures of Yosemite National Park timed to Pink Floyd, Joni Mitchell, and Frank Zappa. In this lesson, the Park Service learned that accommodation was the more ethical and practical solution to a cultural rift. Currently, there is no signage that commemorates the effect the “Hippie Invasion” of 1970 had on park operations. As far as I have been told, there has been no programming that has told the story. I’ve presented the story at campfire programs, and I’ve been told folks are extremely interested in hearing it. By the end of my summer, I’d like to leave Yosemite with a flexible program outline for future rangers to use to tell this captivating story. The movements of the 1960s are very much still alive. And a journey into Yosemite’s past may help individuals contextualize and connect with how they feel about these movements in the present moment.

As an Interpretive Park Ranger, my job isn’t to educate but to connect people with history and nature. In the end, I’m just a storyteller. I give thanks to the fact that I am surrounded by a whole army of extremely intelligent and passionate group of co-workers. Here in Yosemite, if I’m not hiking & or fighting for my life climbing on a granite wall, chances are a much wiser and more experienced ranger is teaching me something new. That is the biggest takeaway from the National Park Service. If you’re interested in being a lifelong learner, I encourage you to apply. Ecologists, wilderness rangers, and cultural resource folks, every day there is something new to be learned.

Dr. Sola asked if I could suggest advice for students that I wished I had when I was a student.. It took some reflection, but my suggestion is never stop learning beyond the classroom. Mark Twain once said “I have never let school interfere with my education.” Talk to strangers on the side of the street. Go out of your comfort zone to speak to folks that don’t necessarily align with your world views. The skills gained from those interactions are valuable and will make you more employable if you’d like to work in public history. I believe my conversations with random people on Euclid Avenue will always be some of the biggest lessons learned at Cleveland State University.

“The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.”

The Grizzy Giant, Yosemite’s oldest Giant Sequoia Tree. Scientists estimate that it is about 2,900 years old.

osemite Valley’s Tunnel View. On the left is El Capitan, the world’s second largest rock monolith. On the right is Bridal Veil Falls. In the far distance is the iconic Half Dome.